"Oh yeah Motorola exists" - Revelations made in CSAW CTF 2021

Published on

Table of Contents

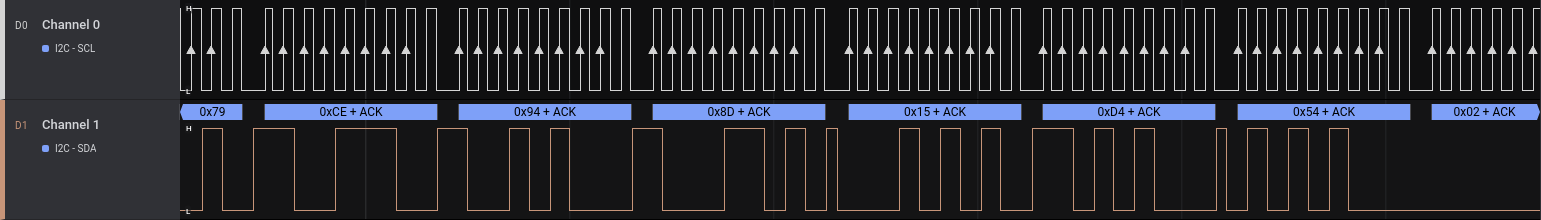

A mildly interesting challenge that touches (very briefly) on serial communication. But given that the files are .sal files, we can use the trusty old Saleae’s logic analyser to help decode everything.

TL;DR: Use Saleae to extract information, be reminded that Motorola exists and created S-records, break the information down, use Ghidra to disassemble and decompile the machine code, and make sense of everything to eventually obtain the flag.

Introduction

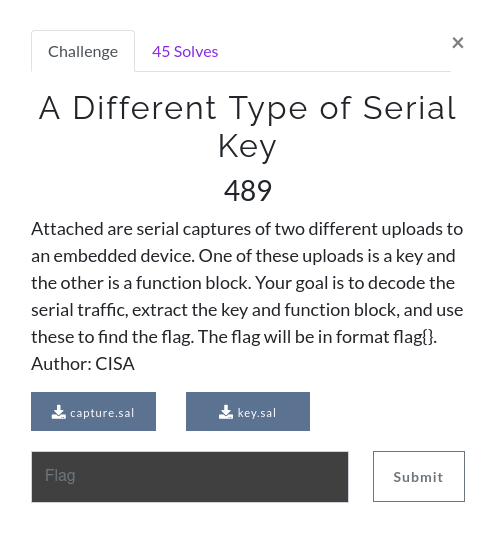

The challenge gives us two .sal files, and based solely on the challenge description, capture.sal gives us a function block, and key.sal gives us a key of some kind. This seems pretty straight forward, so time to get on extracting.

Extraction

key.sal

First, we’ll take a look at key.sal, and see what we can get.

There are only two channels to look at, and given that one channel (channel 0 in white) seems to have pretty consistent rises and falls, it’s safe to say that this is the clock. Leaving channel 1 (the orange channel) to be the data channel we need to collect. Thankfully, figuring out which protocol could be used isn’t too difficult given this information, and just a casual click through all the possible analysers Saleae provides, leads us to I2C being the best candidate for this capture.

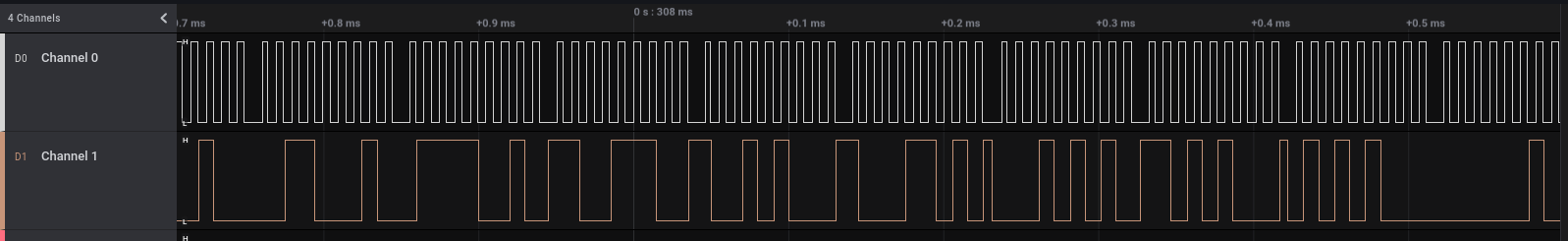

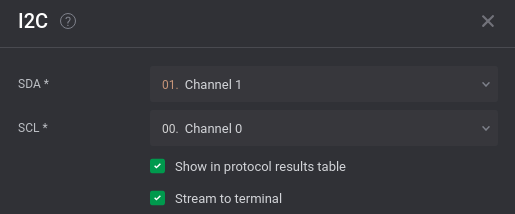

Here we have assigned our clock (SCL) to channel 0, and data (SDA) to channel 1. Applying those settings gives us the the above.

Applying those settings gives us the the above.

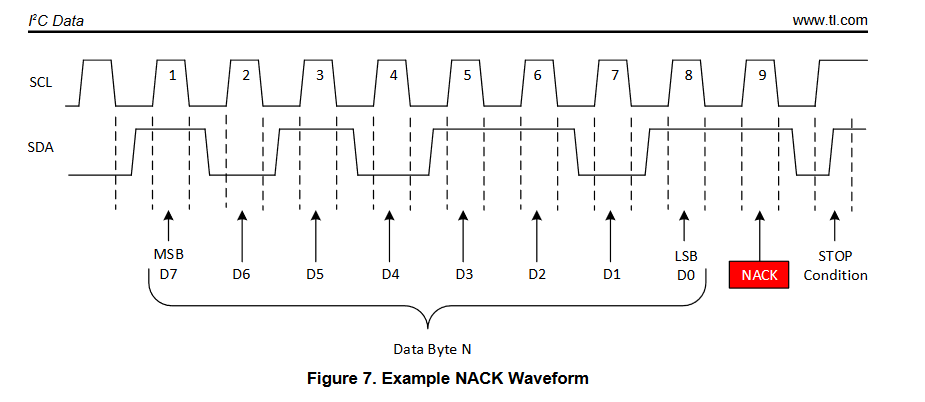

Even though it’s not strictly necessary to know much/anything about I2C, here’s a great diagram from Texas Instruments

that matches what we see in the capture. We can see that SCL is broken into groups of 9 periods (rise and fall of the clock), which matches to I2C’s 8 bits of data, plus an acknowledge bit (each period of the clock transmits one bit).

Looking at the output terminal of the analyser, we get the following information:read to 0x08 ack data: 0x59 0x57 0x72 0x31 0x79 0xCE 0x94 0x8D 0x15 0xD4 0x54 0x02 0x7C 0x5C 0xA0 0x83 0x3D 0xAC 0xB7 0x2A 0x17 0x67 0x76 0x38 0x98 0x8F 0x69 0xE8 0xD0

Since there isn’t anything that can be done to these hex strings, it’s probably safe to assume that’s all for now regarding key.sal - onwards to capture.sal!

capture.sal

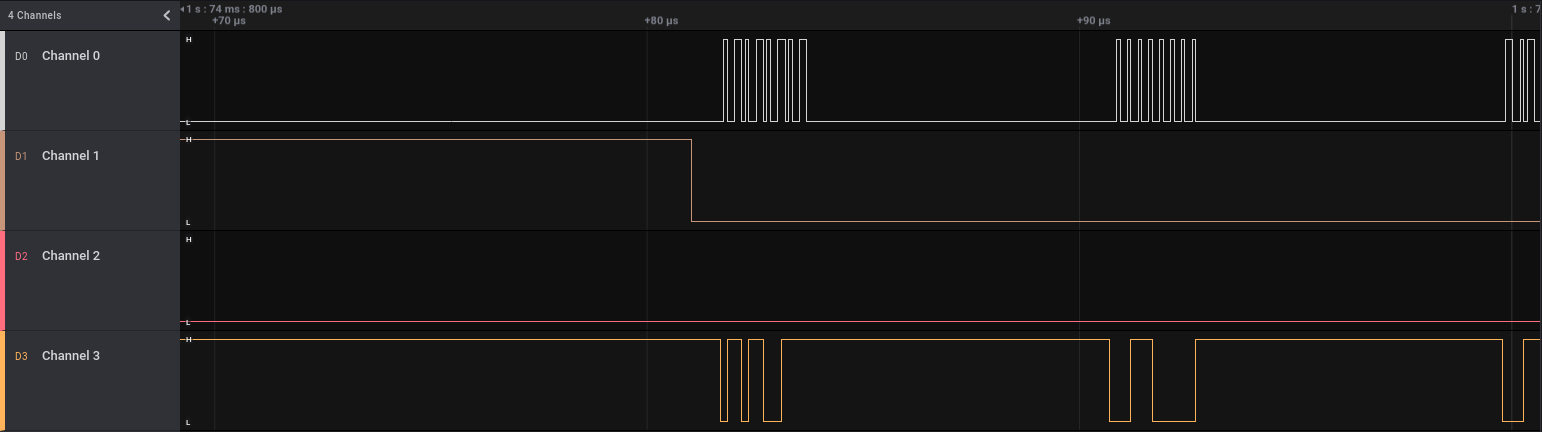

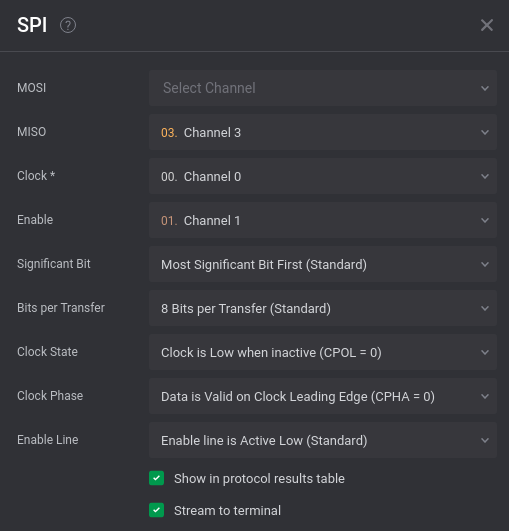

Giving the capture a look, there are clearly two blocks of information being sent. Since this capture uses the same number of channels, and each channel has the same behaviour across the two blocks, it’s safe to assume the same protocol is being used within this capture. Given that there are more than 2 channels, we can rule out I2C. We just need a closer look at what’s going on in each channel. Upon closer inspection, we can see a good amount of squiggly lines. Just from the image alone, we can see that channel 0 is probably a clock, channel 1 is some enable line (active low), channel 3 is data, and channel 2 is dead to us. Now some amount of scrolling through Saleae’s logic analyser will lead us to SPI.

Upon closer inspection, we can see a good amount of squiggly lines. Just from the image alone, we can see that channel 0 is probably a clock, channel 1 is some enable line (active low), channel 3 is data, and channel 2 is dead to us. Now some amount of scrolling through Saleae’s logic analyser will lead us to SPI.

Based on the information we do have, we can plug them into the settings for SPI. Again, knowing SPI in detail is not necessary, but a here's a great video

on the basics of SPI.

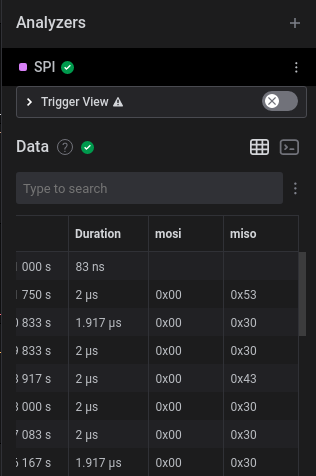

Taking a look at the analyser’s output table, we can see that the data (miso in my case) seems quite ASCII like. There are many useless facts stored in my brain, and knowing that 0x30-0x39 represents numbers 0-9 is one of them. So converting all the hex to ASCII output, gives us the following:

Block 1:

S00C00004C6F63616C204B6579BF

S221020018423B165105BDAAFF27DB3B5D223497EA549FDC4D27330808F7F95D95B0EC

S5030001FB

Block 2:

S0210000506F77657250432042696720456E6469616E2033322D42697420537475620E

S12304EC9421FFD093E1002C7C3F0B78907F000C909F000839200000913F001C4800012C7E

S123050C813F001C552907FE2F890000409E0058813F001C815F000C7D2A4A1489290000FF

S123052C7D2A07743D20100281090018813F001C7D284A14892900003929FFFD5529063EC7

S123054C7D2907747D494A787D280774813F001C815F00087D2A4A14550A063E9949000074

S123056C480000BC815F001C3D205555612955567D0A48967D49FE707D2940501D29000317

S123058C7D2950502F890000409E0058813F001C815F000C7D2A4A14892900007D2A077476

S12305AC3D20100281090018813F001C7D284A1489290000392900055529063E7D2907743F

S12305CC7D494A787D280774813F001C815F00087D2A4A14550A063E99490000480000408D

S12305EC813F001C815F000C7D2A4A14890900003D20100281490018813F001C7D2A4A145A

S123060C89490000813F001C80FF00087D274A147D0A5278554A063E99490000813F001CA1

S123062C39290001913F001C813F001C2F89001C409DFED0813F00083929001D3940000040

S11B064C9949000060000000397F003083EBFFFC7D615B784E80002060

S503000CF0

What in the world are all these S’s

This looks very similar to Intel's hex format (.hex files), which essentially allows for machine code to be written into a chip’s ROM. However, instead of semicolons, there are S’s in this case, which is very much not Intel hex-like. This calls for a round of intense searching.

Research

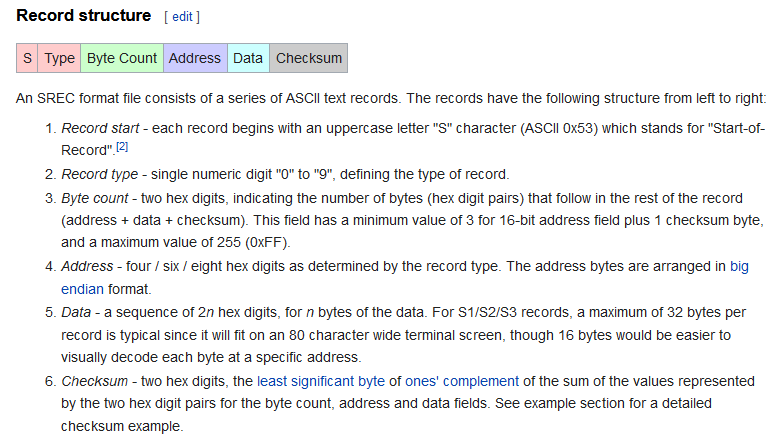

Whip out the keyboard, it’s time to search the internet for what these two blocks really are. Searching up s instead of semicolon hex file gives a couple sites mentioning “S-records”, which is very promising. However, if you’re feeling efficient, S hex files will present the wikipedia page for S-records (originally created by Motorola!). Taking a look at SREC confirms that we’ve hit the jackpot. After spending quite a bit of time reminiscing about some great old Motorola phones

, we can wipe off that sweat from the heavy round of researching, because now we’ll apply our new found knowledge to the two blocks.

Apply

Based on the record structure shown, we can break each block into the appropriate records, and work from there:

Based on the record structure shown, we can break each block into the appropriate records, and work from there:

Block 1:

| S | Type | Byte Count | Address | Data | Checksum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 0 | 0C | 0000 | 4C6F63616C204B6579 | BF |

| S | 2 | 21 | 020018 | 423B165105BDAAFF27DB3B5D223497EA549FDC4D27330808F7F95D95B0 | EC |

| S | 5 | 03 | — | 0001 | FB |

Block 2:

| S | Type | Byte Count | Address | Data | Checksum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 0 | 21 | 0000 | 506F77657250432042696720456E6469616E2033322D4269742053747562 | 0E |

| S | 1 | 23 | 04EC | 9421FFD093E1002C7C3F0B78907F000C909F000839200000913F001C4800012C | 7E |

| S | 1 | 23 | 050C | 813F001C552907FE2F890000409E0058813F001C815F000C7D2A4A1489290000 | FF |

| S | 1 | 23 | 052C | 7D2A07743D20100281090018813F001C7D284A14892900003929FFFD5529063E | C7 |

| S | 1 | 23 | 054C | 7D2907747D494A787D280774813F001C815F00087D2A4A14550A063E99490000 | 74 |

| S | 1 | 23 | 056C | 480000BC815F001C3D205555612955567D0A48967D49FE707D2940501D290003 | 17 |

| S | 1 | 23 | 058C | 7D2950502F890000409E0058813F001C815F000C7D2A4A14892900007D2A0774 | 76 |

| S | 1 | 23 | 05AC | 3D20100281090018813F001C7D284A1489290000392900055529063E7D290774 | 3F |

| S | 1 | 23 | 05CC | 7D494A787D280774813F001C815F00087D2A4A14550A063E9949000048000040 | 8D |

| S | 1 | 23 | 05EC | 813F001C815F000C7D2A4A14890900003D20100281490018813F001C7D2A4A14 | 5A |

| S | 1 | 23 | 060C | 89490000813F001C80FF00087D274A147D0A5278554A063E99490000813F001C | A1 |

| S | 1 | 23 | 062C | 39290001913F001C813F001C2F89001C409DFED0813F00083929001D39400000 | 40 |

| S | 1 | 1B | 064C | 9949000060000000397F003083EBFFFC7D615B784E800020 | 60 |

| S | 5 | 03 | — | 000C | F0 |

Now to analyse what each record means. Thankfully it’s quite simple:

S5we can just ignore, since it only tells us how many S1/2/3 records there are (basically number of data records).- As mentioned above,

S1andS2are data records, the only difference is that S2’s address size is 6 bytes. S0is very helpful, as they’re header records. It tells us information about each block. Given that each S0 record’s data field looks very ASCII like, let’s decode:- Block 1:

Local Key - Block 2:

PowerPC Big Endian 32-Bit Stub

- Block 1:

Very intriguing. There seems to be another key (that’s separate to the key we got from key.sal), so we’ll set that aside and take a look at block 2. It looks like there’ll be at least a little PowerPC fun! Good thing I know a creature that knows PowerPC.

The programming-y bits

Loading up Ghidra

Now, reversing the hex codes to the appropriate machine code instructions by hand would be, to put it simply, complete insanity. Luckily Ghidra can help with not just the disassembly, but also the decompilation. This allows us to deal with PowerPC with little to no PowerPC knowledge.

Given that I know basically nothing about PowerPC, the decompiler thankfully gives plenty of information as to what’s going on (I’ve changed some variable names):

void UndefinedFunction_00000000(int param_1,int param_2)

{

uint index;

for (index = 0; (int)index < 0x1d; index = index + 1) {

if ((index & 1) == 0) {

*(byte *)(param_2 + index) =

*(byte *)(param_1 + index) ^ *(char *)(local_key + index) - 3U;

}

else {

if ((int)index % 3 == 0) {

*(byte *)(param_2 + index) =

*(byte *)(param_1 + index) ^ *(char *)(local_key + index) + 5U;

}

else {

*(byte *)(param_2 + index) =

*(byte *)(param_1 + index) ^ *(byte *)(local_key + index);

}

}

}

*(undefined *)(param_2 + 0x1d) = 0;

return;

}

Taking a look at this, it seems to XOR (^) each byte of param_1 against the local key (with some small adding/subtracting depending on the index) and stores it in param_2. Clearly, param_1 is where the key from key.sal comes in and param_2 should hopefully be the flag.

Trust the python

All that needs to be done is to plug the keys into the C code and hopefully get the flag. But for whatever reason, my brain decided it wanted to work with snakes instead.

key = [0x59, 0x57, 0x72, 0x31, 0x79, 0xCE, 0x94, 0x8D, 0x15, 0xD4, 0x54, 0x02, 0x7C, 0x5C, 0xA0, 0x83, 0x3D, 0xAC, 0xB7, 0x2A, 0x17, 0x67, 0x76, 0x38, 0x98, 0x8F, 0x69, 0xE8, 0xD0]

local = [0x42, 0x3B, 0x16, 0x51, 0x05, 0xBD, 0xAA, 0xFF, 0x27, 0xDB, 0x3B, 0x5D, 0x22, 0x34, 0x97, 0xEA, 0x54, 0x9F, 0xDC, 0x4D, 0x27, 0x33, 0x08, 0x08, 0xF7, 0xF9, 0x5D, 0x95, 0xB0]

flag = ""

for i in range(29):

if (i & 1) == 0:

flag += chr((key[i] ^ local[i]-3))

elif (i % 3) == 0:

flag += chr((key[i] ^ local[i]+5))

else:

flag += chr(key[i] ^ local[i])

print(flag)

In the end, we finally get the flag we’re after!

Flag: flag{s3r14l_ch4ll3ng3_s0lv3r}